In 1992, an uprising occurred after a jury acquitted the Los Angeles Police Department of charges related to brutally beating a young Black man named Rodney King. After the judge announced the verdict, numerous buildings were set ablaze, and upwards of 2,300 people were injured in the civil unrest that persisted for several months. Today, the public mostly remembers the event, dubbed the “1992 LA Riots,” for the ensuing chaos after that verdict. However, fewer people recognize that there were additional reasons for the event.

At age the young age of 15, while shopping for some orange juice, Latasha Harlins was shot in the back and killed by Du Soon-Ja, a Korean woman who accused Harlins of stealing from her convenience store in South Los Angeles. Allegedly, Du had threatened other children with weapons before Harlins, but this time she pulled the trigger. Two months after the incident, like the LAPD, the judiciary eventually handed Du an incredibly light sentence. Hence, many believe this judicial decision also contributed to the harsher treatment experienced by Koreatown during the riots, with reportedly increased violence, looting, and arson in the area. In particular, looters targeted Du’s store, burning it to the ground. After the chaos, it never reopened.

The 1992 LA Riots merely exemplify tensions between Korean-Americans and Black Americans that continue to manifest in the United States. For many years, some Black Americans have intentionally avoided supporting Korean-owned businesses, and some Korean American business owners have discriminated against their black patrons. However, despite the racial, cultural, and linguistic barriers between the two groups, they share quite a distinct history that would theoretically link them.

Over the past 200 years, both Korean and Black Americans have experienced tremendous oppression at the hands of hegemonic powers. For example, in the United States, white landowners enslaved millions of people of African descent through the transatlantic slave trade. These enslaved people were overworked, sexually abused, and forced to conform to a white-controlled society. Likewise, thousands of Korean and Korean Americans faced exploitation via Japanese occupation throughout the first half of the 20th century. Their Japanese oppressors forced them to abandon their Korean names, co-opted their historical artifacts, sexually enslaved their youth, and robbed them of their political autonomy. Moreover, once their controllers abandoned the established system, members of these ethnic groups were forced to pick up the pieces and rebuild. As a result, many chose to flee their homeland to seek success in other parts of the world, while others remained in familiar territory. Collectively, shared trauma continues to affect the descendants’ current circumstances negatively.

Moreover, once their controllers abandoned the established system, members of these ethnic groups were forced to pick up the pieces and rebuild. As a result, many chose to flee their homeland to seek success in other parts of the world, while others remained in familiar territory. Holistically thinking, Koreans and African Americans share a comparable history concerning the erasure of their identities and theft of their bodily autonomy. Hence, aside from noticeable physical and social differences between the two cultures, many would assume that there is some affinity between them.

Nevertheless, a rift still manifests between the groups. A systemic socio-economic divide exists between Korean Americans and their Black American peers, furthering the perceived dissimilarity between the populations within the United States. Similarily, many Korean celebrities continue to culturally appropriate Black culture, which creates outrage and division. Some of the biggest names in the Korean popular music industry have adopted culturally insensitive hairstyles and artificial personas that mimic Black culture. Just last month, netizens exposed Jennie from Blackpink for wearing cornrows, a traditional African hairstyle with ties to chattel slavery, in a promotional advertisement for a new HBO show. Despite Blackpink being one of the most popular female groups in the world, she has encountered very few repercussions for these actions. Nonetheless, one significant similarity presents between the two divergent groups: Confucian ideology in response to exploitation.

Historically, Confucianism became integrated into Korean social structures several hundred years ago. Brought over from China in the 13th century, the ideological values of Confucianism rose to prevalence during the Joseon Dynasty. Many ideas promoted by the ideology, such as age-based hierarchy and social position, were attractive to leaders of the time. However, as a response to the rising popularity of religion, especially Buddhism, a new form of philosophy eventually became prevalent: New Confucianism. Still relying on many traditional Confucian values such as filial piety but utilizing a metaphysical-based ethical system, this specific form of Confucianism has had a lasting effect on Korean society, even today.

Particularly over the past century, Korean political thinkers have embraced Confucian ideals in response to the Japanese occupation and the discrimination that accompanied forced modernization. Kim San and other leaders criticized their oppressive system through Confucianism and a leftist perspective towards ending their rule. In addition, leaders integrated Confucian ideals into the Korean civil code even after the Japanese government’s colonial rule ended. They rebelliously employed its teachings as a rebuttal against the controlling regime that subjugated them and the Westernization policies that sought to oppress them. Thus, they adopted policies such as the prohibition of marriage between people of the same last name, which originated from the Confucian ideal that “when a man and a woman (in marriage) share the same surname, their offspring will not flourish.” Via these traditionalist policies they contested their oppressors and found a unique, hybrid political identity.

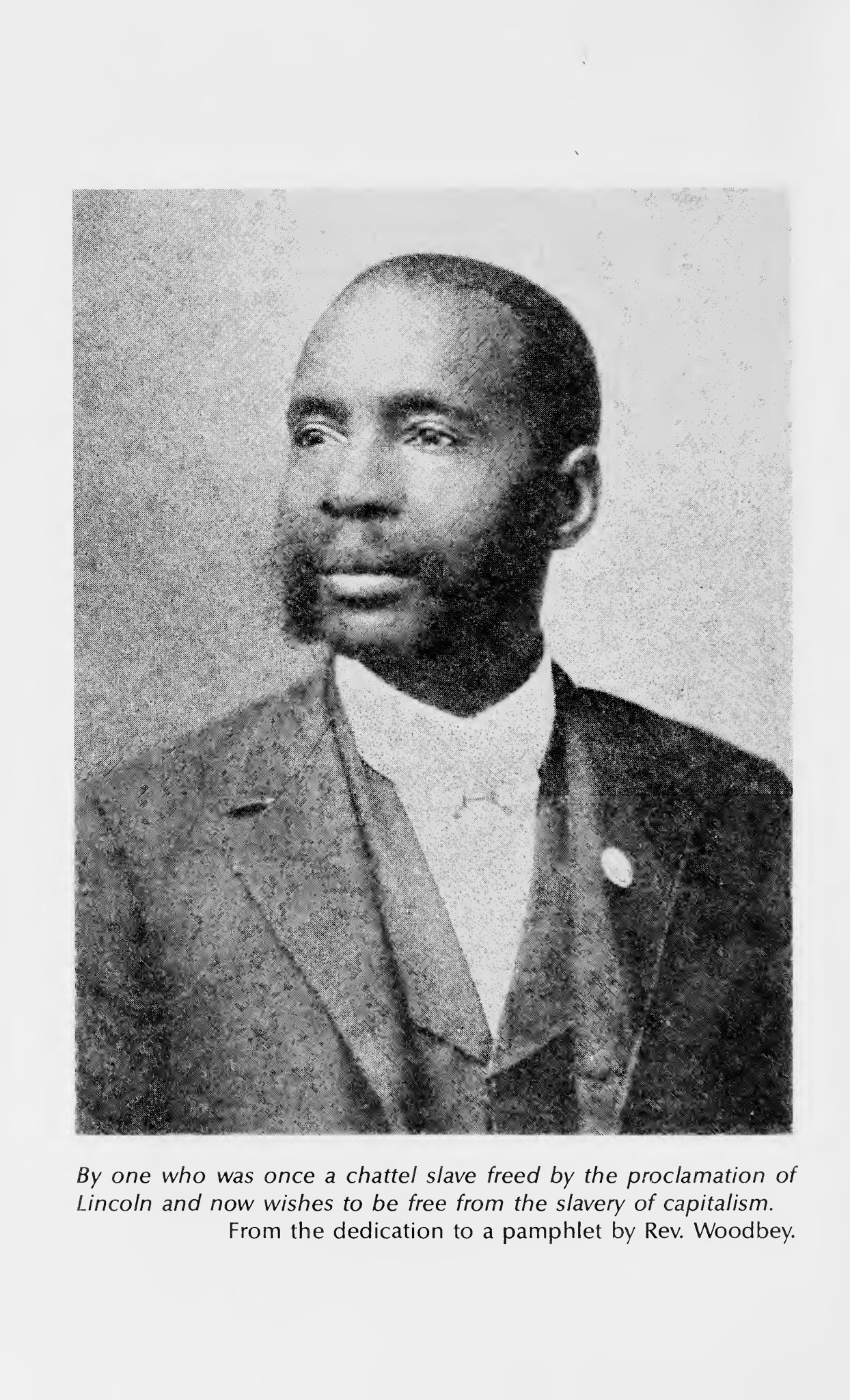

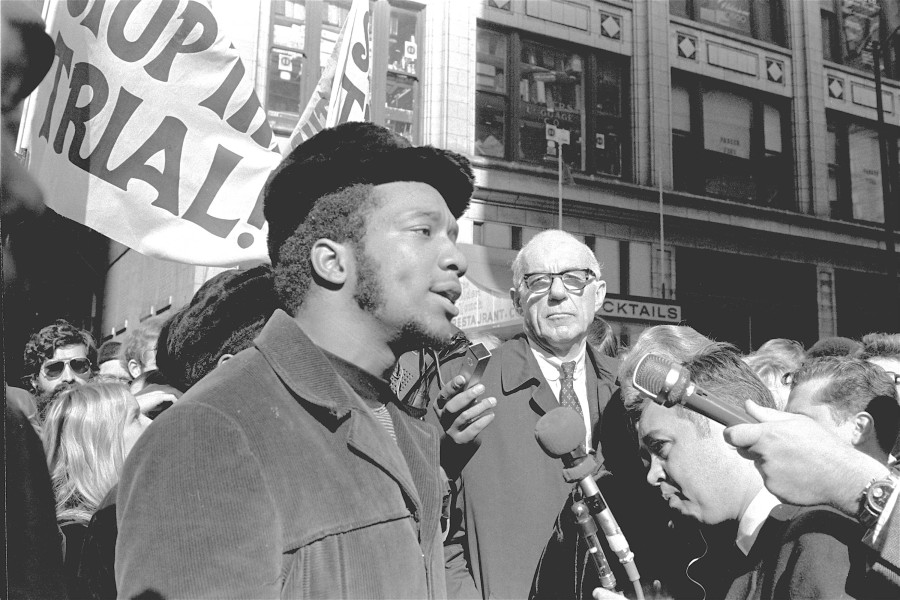

Beginning in the early 1900s, as a response to the historical subjugation of their people, many Black and Korean activists embraced Confucian ideas in their effort to combat prejudice. While rarely emphasized in American history, Chinese Confucian thought strongly influenced the fight against American racism within the Black Power movement. Many prominent Black activists like Stokely Carmichael, Fred Hampton, and George W. Woodbey saw Confucian ideals and Chinese socialism as a solution to the prejudice in the everyday lives of Black Americans.

Although Confucius never spoke on issues of race, many of these Black activists were initially drawn to his beliefs. Specifically, various thinkers utilized Confucius’s teachings in the fight against their oppressors’ support of Christianity. The Pittsburgh Courier, a prominent weekly Black newspaper, once analogized “the teaching of Confucius: ‘Do not unto others that you would not have them do to you,'” to a biblical statement of Jesus Christ:” ‘Do unto others, that you would they should do unto you.'” Drawing comparisons to the inequalities in Asia, they embraced Confucian beliefs to parallel the qualities they saw as necessary for change. For many, Confucianism’s teachings of reciprocity and hierarchal social order became integral to their philosophy for combatting racism. Essentially, “Confucian and Christian teachings represented a moral standard that white society should abide by,” and Confucius’s non-white status made it all the more attractive.

Furthermore, even those who never specifically referenced Confucius embraced the values indirectly through their affinity for Chinese political thought. For example, well-known Black activist and educator, Frederick Douglass, was “confident that the Chinese, emboldened by Confucianism, would join African Americans in resisting this new form of slavery.” He viewed Confucianism as a solution that opposed the Christian values that white racists used to subjugate and enslave Black people. Consequently, these teachings and connections became embedded within Black society and strongly influenced other Black thinkers until the 1950s. Thus, even though most people studying these historical political movements often overlook the role that Confucian thought played in shaping the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, it manifested as a rebellious and persuasive ideology among various activists.

Altogether, when considering both Black Americans and Koreans, Confucianism cannot be stripped from their political thought. For both groups, prominent leaders sought freedom from their subjugators through similar political and social ideologies. Moreover, their tools came from a similar source: Chinese Confucian thought. Fundamentally, they used such philosophy as a source of morality and inspiration, which helped them tackle oppression. Thus, even though modern political conflicts between the two groups largely obscure these similar origins, an ideological basis connects the two distinct groups.

With such connections in mind, it denotes a very distinct Korean concept called 닮음(Dalm-eum). Translated best into English as “resemblance,” dalm-eum demonstrates how these two persecuted cultures converge in their ideological history. Despite the ongoing tensions between Black Americans and people of Korean descent and systemic prejudice that manifests as a perceived division between the cultures, similar histories and political motives leave room for collaboration throughout the continual racial discrimination. Via dalm-eum, these groups have even more reason to tear down the walls between them and function alongside each other. Hence, whether through the collaboration of the “Stop Asian Hate” and “Black Lives Matter” movements or some other historical interactions, they have a political foundation to converge in solidarity toward a similar goal.

WORKS CITED

Kevin N., Cawley. 2021. “Korean Confucianism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University: Metaphysics Research Lab. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/korean-confucianism.

Suzanne, Sng. 2022. “Blackpink’s Jennie Accused of Cultural Appropriation for Having Cornrows in HBO Series the Idol | the Straits Times.” straitstimes.com, July 19, 2022. https://www.straitstimes.com/life/entertainment/blackpinks-jennie-accused-of-cultural-appropriation-for-having-cornrows-in-hbo-series-the-idol.

Yong, Chen. 2012. “The Presence of Confucianism in Korea and Its General Influence on Law and Politics.” In ¿Es El Confucianismo Una Religión? La Controversia Sobre La Religiosidad Confuciana, Su Significado Y Trascendencia. El Colegio de Mexico.

Yoon, In-Jin. 1998. “Who Is My Neighbor?: Koreans’ Perceptions of Blacks and Latinos as Employees, Customers, and Neighbors.” Development and Society 27 (1): 49–75. https://doi.org/http://www.jstor.org/stable/44396776..

Zhang, Tao. 2021. “The Confucian Strategy in African Americans’ Racial Equality Discourse.” Dao 20 (2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11712-021-09778-9.

Leave a Comment